Who are the people exploring for gold in the back and beyond of Bendigo? Marjorie Cook visits Santana Minerals’ Central Otago field office to meet the crew.

Bendigo – not to be confused with that other, Australian Bendigo – is big-sky, mountain-high, merino sheep country and home to fewer than 100 people.

The other Bendigo across the ditch used to be a sheep station but is now a city of 110,000 and one of Victoria’s fastest growing regional centres.

Both Bendigos emerged from the 19th century gold rush.

Central Otago’s Bendigo was named by Victorian-era miners who moved from Australia to test their fortunes in a new land and discovered what became Otago’s (and New Zealand’s) richest goldfield.

Between 1862 and the late 1880s, hundreds of people lived, worked, and partied in three communities – Bendigo Gully, Welsh Town and Logan Town.

In 2008, the area became a Department of Conservation reserve.

While Bendigo, Australia grew into a city with significant finance, health, tourism and primary industries, Central Otago’s Bendigo population dropped from about 500 people in 1878 to 140 by 1881.

By the 1940s, the deep mine shafts and stone cottages had been abandoned to the karearea, mokomoko, kanuka – and sheep.

Otago’s archives are packed with stories about the 18th century goldfields people.

Many came from Australia, California, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, England and China.

In the last two decades, much has also been published about the 21st century “rush” to the area.

Farmers have arrived from all over New Zealand to create new livelihoods from dairying, cherry orchards, vineyards, olive groves, and fields of saffron.

In 2012, a small team commenced mineral exploration around nearby Cromwell.

By late 2020, the team had expanded with new people arriving to work for Santana Minerals drilling and exploration company.

They operate from a leased bit of land on Bendigo Station, in a refurbished Ministry of Works house from Tarras.

They have upgraded farm tracks, popped up some portable drill rigs and dotted the hills with short white sticks.

This year, the company released a series of increasingly positive updates to the Australian Stock Exchange, announcing ”exceptional” and ”spectacular” results from its exploratory drilling programme in the Bendigo-Ophir goldfield.

Assays from three holes in particular had confirmed the company’s expectation of high-grade gold and continued success. So who are these modern day gold explorers? Where are they from? And what are they actually doing?

Starting at the top, there’s Santana Minerals’ Auckland-based director and project manager Kim Bunting, who is supported by another Canterbury-based project manager Hamish McLauchlan.

Mr Bunting commutes to Tarras regularly to lead a growing team of geologists, field technicians and administrators.

He’s from the North Island but has had a long association with mineral exploration in Central Otago, with geologist Mark Hesson of Alexandra.

The original operating company, Matakanui Gold, is now a 100% subsidiary of Santana, an Australian company that has a 45% New Zealand-based shareholding.

Before 2020, Matakanui Gold had been exploring the southern end of the Bendigo-Ophir field.

Attention has now shifted to the northern end of the field and about 12 Santana employees are based at Bendigo.

A Waihi-based drilling contractor Alton Drilling employs about 18 other people to work on the exploration project.

Now Santana has announced it wants to expand its drilling programme, Mr Bunting needs to increase his workforce.

But he has been struggling to find the people he needs for full time and contract positions. He has advertised, without much success.

Unaffordable housing is a major deterrent for people to move to the Central Otago and Queenstown Lakes districts, despite an abundance of jobs.

So Santana purchased a “donga” – Australian slang for a prefabricated house – and put it in its Bendigo yard for field staff to use until they find a home in a town nearby.

Another solution was to shoulder tap family and friendship groups from Taupo or Dunedin, but Mr Bunting still wants more people.

“I can’t find more field assistants. I just can’t find them. We need them for core cutting, field work and fixingroads. It has been hard,” Mr Bunting said.

The crews working for Waihi-based contractor Alton Drilling Ltd are also based in Santana’s leased yard on Bendigo Loop Rd, at the foot of the Dunstan Mountains, but are rarely seen.

Alton’s three rigs, which look like small cranes, work around the clock in the hills above Shepherds Creek, near the historical Rise and Shine battery.

The rig teams switch shifts at 6am and 6pm and live in Cromwell and Tarras.

So far nothing except Covid – not even the miserable winter conditions – has stopped the rig teams.

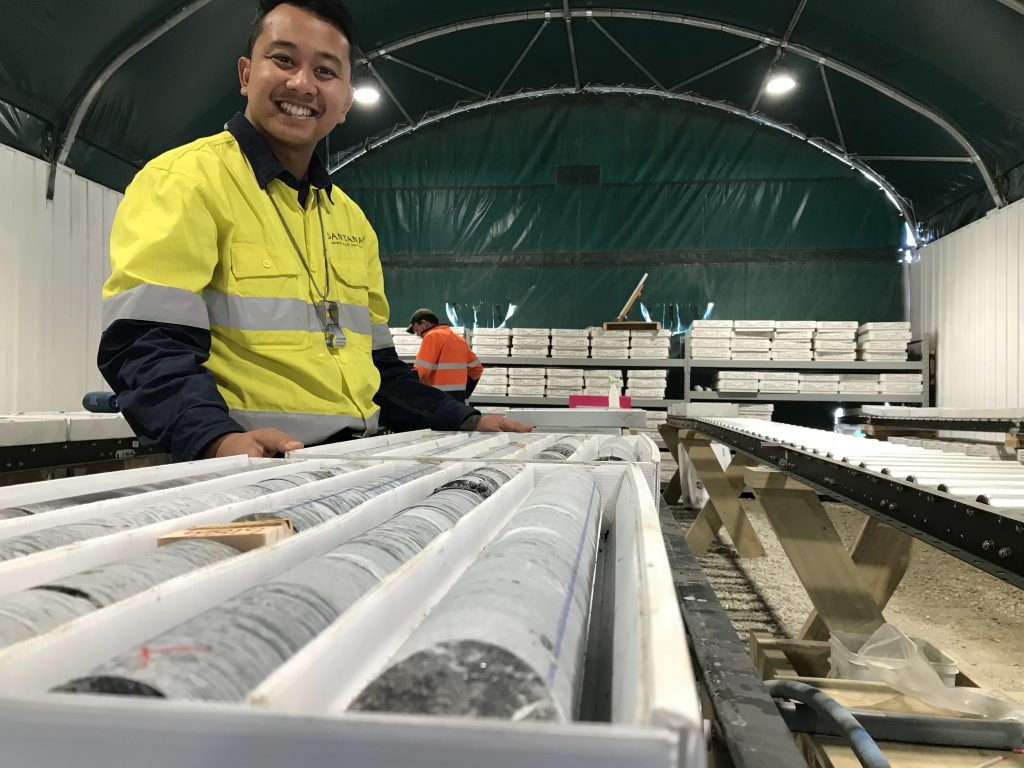

In the June quarter alone, they delivered 7km of quartz and schitz samples to Santana’s yard on the flat for geological analysis.

The senior geologist is Paul Becker, of Alexandra, who works alongside Patra Bratakusuma, and his sister Gea Bratakusuma.

The Bratakusuma siblings hail from Taupo. Their father, originally from Indonesia, works in the geothermal industry, and they’ve both got a BSc in geology from Auckland University.

Patra also has a MSc in geology and was convinced by Mr Bunting in 2020 to put his PhD studies on hold and work for Santana.

Patra’s partner Rio Matsuda, from Japan, also moved to Bendigo to work as a field technician. Gea moved down in February and to continue the Taupo connection, a family friend Hamana Judkins-Tua, an experienced geothermal industry worker, arrived in June.

Experienced alluvial gold technician Mark Ward, from Gore, also joined the team and Otago University geology student Joe Cunningham works as a field assistant, when his studies permit, and hopes to join the team full time when he graduates.

Patra intends to return to Auckland to complete his PhD, “but not at this stage.”

“It is a little quieter here. Less traffic anyway,” he grinned.

Patra does not get into the hills as often as he likes, but when he does, he loves it.

“I love the interaction with the drillers, finding new things. Every hole is different. We discover new things. And there is always a nice view,” he said.

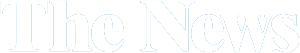

The geologists measure the structures found in the core samples, check their integrity and mark where field technicians should cut them with a diamond circular saw.

The geologists, metre by metre, look at the types of features. We see if there are quartz tension gashes . . . we measure the veins to see if there are any fractures or joints, we measure the angle of the shear. And we log everything we see,” Gea said.

The geologists also do mapping and soil sampling to decide where the rigs should drill next.

Half of each core sample is retained for quality control and assurance purposes. The other half is sent away to a Westport laboratory for prepping, crushing and grinding before the sample is forwarded again to a Waihi laboratory for further analysis.

Samples leave Bendigo by courier once or twice a week, and the laboratories return what they don’t use to Santana for their growing library of reference material.

Field technicians then further analyse the pulp with an x-ray machine for other naturally occurring minerals, such as silver, zinc and arsenic, before storing the returned samples, again for quality control and assurance.

Field officer Roderick MacLeod leads the field technicians. He has a background in road construction and moved up from Dunedin just over a year ago.

His partner MacKenzie Foster left her career in the beauty industry to work for Santana as an administrator.

Mr MacLeod marvels his ancestors used horse and cart to travel the same Bendigo tracks he now maintains.

“There has been a big change since back then,” he said.

“I would recommend working for Santana. For field technician staff we would almost take anyone. Training will be provided to anyone starting out, he said.

Another job is to cap the drill holes, sow seeds and plant vegetation to restore the dryland alpine vegetation, as directed by environmental consultant Dr Barrie Wills of Alexandra.

Bunds have been built on dangerous corners to make sure vehicles don’t slide off the farm tracks during miserable winter conditions, speed signs have gone up on the steep sections of the unsealed public Thomson Gorge Rd, and potholes caused by recent heavy rain are being filled.

Mr Judkins-Tua is already loving his new life living in a “donga” in the high country.

“Essentially, I pretty much help out where I am needed, resurfacing roads at the moment after the heavy rain, core cutting and driving the heavy machinery. Compared to Taupo, I prefer it here so much more. I can go skiing,” Mr Judkins-Tua said.