Academic history has been made in Alexandra, and the man at the centre of it is a special mix of traditional academia and grassroots medicine.

Prof Garry Nixon, who works at Dunstan Hospital in Clyde, delivered his inaugural professorial lecture at Earnscleugh Hall on Monday evening.

While professorial lectures have been delivered on marae, it is believed it was the first time in New Zealand one has been made in a country hall.

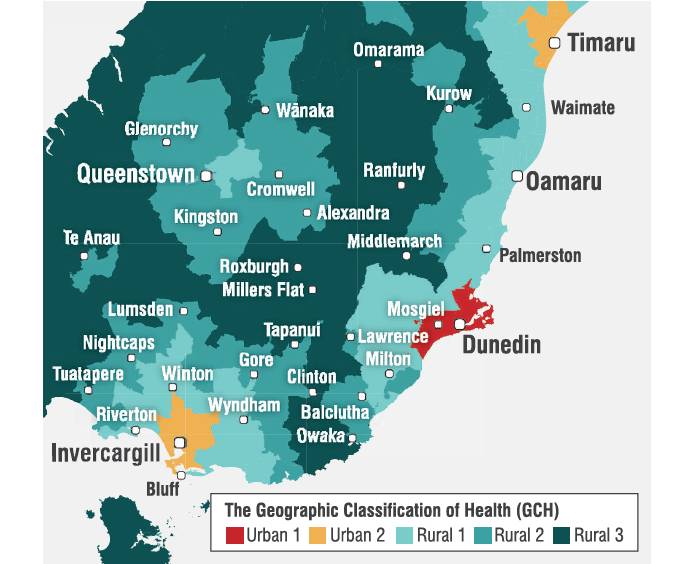

Prof Nixon and his team have developed the geographic classification of health (GCH) — an updated system that more accurately defines urban and rural areas and means health outcomes and access to services can be monitored more accurately.

They developed the classification with five categories, two urban and three rural, that reflect degrees of reducing urban influence and increasing rurality.

The GCH applies these categories to all of New Zealand. ‘Urban 1’’ to ‘‘Urban 2’’ are based on population size and “Rural 1’’ to ‘‘Rural 3’’ are based on drive time to the closest major, large, medium and small urban areas.

The purpose was to find out how healthy rural New Zealanders were compared with city dwellers and how rural people used health services and how good their access was to those services, he said.

‘‘Interestingly, in New Zealand that’s never been very well looked at in the past.’’

Historically, data suggested health outcomes for rural and urban people were very similar.

However, through teaching and talking with colleagues around the country, it was pretty clear the data did not really make sense and was completely different from what was being seen in other countries.

His research explored health outcomes in depth and it quickly became clear the way urban and rural were defined was problematic as classifications systems were not designed for healthcare and produced some ‘‘silly results’’.

He gave the example that if you looked out your window and saw houses you were urban, whereas if you saw paddocks you were regarded as rural.

Under that definition, Hanmer Springs, 132km from Christchurch, was designated urban while someone on the Taieri Plain, 26km from Dunedin Hospital, was rural.

Most people were unaware of the research being done by academic staff at Dunstan Hospital, including not only Prof Nixon’s work on health outcomes and improving health services for rural communities, but also into physiotherapy and nursing. The geographic classification of health had drawn great uptake and was adopted by the Ministry of Health and the new rural health strategy.

Using the GCH showed that, like Canada and Australia, health outcomes for rural people were poorer than for those in urban areas, Prof Nixon said.

Identifying the problem was the first step to solving it. The data showed rural people in New Zealand were much less likely to be admitted to hospital than those in the city, which was not the case in Australia and Canada.

‘‘That shows us the rural hospitals that we have left are really important. The communities they’re serving have poorer access to hospitals than people in the city.’’

Why that was the case was hard to quantify, he said.

‘‘Maybe rural general practice is better at keeping people out of hospital.’’

However, some of it could relate to access, where getting to hospital was so difficult people did not go. It was probably a combination of factors, but it was important to realise rural people had poorer access to hospitals.

The shortage of rural GPs contributed to the problem.

‘‘That’s a grumbling, chronic crisis that’s been there for a really, really long time.’’

Fixing that complex problem needed intervention at several levels, Prof Nixon said.

‘‘We know what needs to be done but to a large extent in New Zealand we just haven’t done it.

‘‘Or if we have done it, we haven’t done it in a particularly co-ordinated way.’’

Proven interventions were threefold — get children from rural areas to go to medical school, give medical students long-term exposure to rural health and have a dedicated rural medicine career pathway, he said.

In Australia, thanks to invention programmes, rural children were now slightly more likely to go to medical school than those from the city. In New Zealand, pupils from rural schools were half as likely to go than their city cousins.

Once at medical school, if students spent six years in city hospitals they were not likely to consider rural practice. There were programmes in place to change that, Prof Nixon said.

Probably the most important was the rural immersion programme where students spent a year in a rural area.

At the University of Otago, 25 students, about 7% of the class, did that in their fifth year and recently increased government funding meant that could increase to about 35 students.

Students who did the programme were about six times more likely to end up in a rural area.

‘‘The short rotations don’t work. Sending kids for six weeks doesn’t work. They’ve got to spend the whole year.’’

While Queenstown and Balclutha had had rural immersion students for several years, Central Otago’s first group would start next year, spending part of their time in private practice in Alexandra and the rest at Dunstan Hospital.

The third important intervention was dedicated career pathways. Prof Nixon had a big role in setting up the rural training programme for hospital doctors, which had been running for about 15 years. Most of the doctors at Dunstan had been through that programme.

However, no such programme currently existed for general practitioners. The College of General Practitioners was the body responsible and work was being done on it.

That prong was probably the most important thing for small towns such as Roxburgh, he said.